Volume 2 – chapter 9 – part 2 – post 71 – earning some spending money – taken from chapter 4 – into the unknown – part two – a brief sojourn at stoke – consisting of 7 pages from 90 to 96 (446 to 452) edited on Monday, 10 October 2011

My willingness to take any job I could find proved a winner, when I noticed, while in Hanley Park one day, the large dairy company on the far side of the park which might be worth an enquiry, walking in as bold as brass I enquired about a job and was employed there and then on the spot.

Lady luck had smiled on me once again because I had asked for a job at the very moment that one had arisen, though I did not know it at the time. The Clover Leaf Dairy Co Ltd received bulk supplies of milk which they bottled and delivered both on a retail and wholesale basis. The retail manager had a problem over which he was pondering the day I walked in; when he saw me he must have thought I was the answer he was looking for. Most of his fleet of delivery vans had a trouble free route that they covered each day, but there was one that was giving him trouble. This was a neighbourhood called Cobridge where his delivery men had not stayed on the job for very long, and the state of affairs had slowly deteriorated from bad to worse. When the manager found that I knew the area, and that I had a clean driving licence, he offered me the job, though he never told me that there were problems. So the very next day I found myself with a delivery van and an order book out on my route at the crack of dawn.

My van had been loaded with the appropriate products as dictated by the order book, I had standard milk in pint bottles with a silver cap made of metal foil, there was other types of milk, in bottles with a blue cap, green cap, and the top of the range which was called Devonshire double cream which had a gold cap. There were certain customers who preferred the long life homogenised milk which was in a bottle with a metal cap like the caps on lemonade and beer bottles, and there was a regular demand for cream, and orange juice. The system was to deliver each day, then once a week on a Friday afternoon it was necessary to collect payment in accordance with the order book. It did not take me long to find out that in the Cobridge area many of the customers had not paid their milk bill for quite a few weeks. Nor had they been putting out their empty bottles, which was a requirement if they were to get further supplies. Why was this happening in this particular area I wondered, another little mystery to which I found the answer in the first few days? Cobridge it appeared had become a black ghetto with many of the large houses owned by slum landlords, who had packed in an excess of tenants who were living in overcrowded conditions. No wonder the delivery men were not staying on this particular round, it was a nightmare which they did not want, neither did I really, but it was a very convenient job for me, so I resolved to tackle the problem and keep the job until the time came to move on.

For the first week I made the usual deliveries while I watched and observed the local activity; for example I sat in my delivery van and watched the weekly delivery of ethnic foodstuffs. A large furniture type van arrived and sounded its horn, which brought people running from every direction. Everyone carried large basins and jugs, shopping bags and other such containers, in which to carry the food products they purchased from the back of the van. For a few pence the man with the van weighed out a pound of this or two pounds of that, and away went the people with enough basic food to live for another week. Later I spoke to one or two of the locals who told me that the various races could get their needs from this van and for two or three shilling a week could feed themselves better than they had ever been able to do in their countries of origin. These people were a mix of all sorts, African, Indian, Pakistani, West Indian, some of whom were illegal immigrants. None of them worked, but all lived comfortably on the unemployment benefit; one man I spoke to said: “Why should we work when we can live quite well on what this country gives us? If you are sick they take care of you, if you have a problem or a need they look after that as well.” It is strange that people like me were leaving to seek a better life, and here were these newcomers happy to accept much less, as long as they didn’t have to work for it.

The following Friday afternoon I began to knock on doors and demand the money the occupants owed for milk; I knew who to look for because I had seen many of them entering and leaving the houses. At some houses I was met with a complete refusal to cooperate, my response was to tell them in a loud voice heard by all who were hiding inside that no one in that house would get any more milk until those that owed money had paid. Also I informed them that I would refuse them milk until all the empty bottles had been returned. I had been warned not to enter these tenements where attacks and robberies often took place, but with different families living on each floor, it was the only way I could track down those that were taking in the milk and not paying. I stamped loudly and banged on doors and let the occupants know that I would keep on doing this until outstanding debts had been honoured.

In a couple of weeks I had recovered most of the debts and an enormous number of milk bottles, and the company was delighted with the results. Mind you the state of some of those milk bottles was beyond description. At one house I found a small mountain of bottles on the door step, and the things they had used those bottles for beggared belief. Delivering milk was not a pleasant job at the best of times, what with bad weather and the fact that you worked every day of the week it was hardly surprising. The pay was not very good though I have to say that I was finished before midday most days, and I was allowed to drink as much milk as I wanted, free of charge. The particular difficulties I had with the Cobridge district made my job even less worthwhile for such a meagre salary, but after a few weeks I had it running smoothly, and it improved considerably.

This does not mean that there were no further problems, in a locality as repugnant as Cobridge had become there would always be trouble. An example would be the day that I stopped a one of the tenement houses with the usual high load which made it impossible to see out the back of the vehicle. These streets were side roads with very little traffic, so I had developed the habit of standing with one foot on the accelerator and the other on the platform outside the van door when I wanted to move in reverse. From my position I had a good view up and down the street, and at this particular point in the road I could back my vehicle slowly around a corner before setting off back the way I had come. On this particular day a car had parked right up close to my rear and I could not see it because of my big load. The occupants had entered the house next to the one I had been in, so there was no warning when I began to reverse. Moving slowly I had time to stop when my rear touched the car which prevented any real damage, but the glass in the headlight had been broken.

Being unable to get any attention though I sounded my horn and walked about for a couple of minutes, I had no time to waste so wrote my registration and company name on a piece of paper and stuck it under the wipers on the car. Off I went to continue my deliveries then looking in my mirror I saw the same car following me, it then pulled in front of me and stopped across the road. Out of it climbed three black men who stood side by side across the road in front of me, so I leaned out and asked them what they thought they were doing. In a very threatening manner they said I had to go with them, to which I replied: “If this is about the broken headlight you have my details and the company insurance will pay for a replacement.” They did not know anything about insurance so I had to go with them they said. I told them I had work to do so I would not go with them, and if they did not get out of my way I would flatten them into the road. Whereupon I started my vehicle and drove on, and with startled looks of their faces they jumped aside and returned to their car.

On my return to the depot I reported the incident and prepared to go home, but before I did I decided to ring the police station and tell them what happened. After I had explained to the desk sergeant he told me that he had the three black men at the station making a complaint, but I should leave it to him, and he would deal with it. How he dealt with it I never discovered but neither the company or I heard anything more about it.

This job was not an enjoyable one, but it was not all grim and nasty, there were some lighter moments which I still recall with some pleasure. Most of my customers were Pottery people, the warmest and kindest you could meet anywhere.

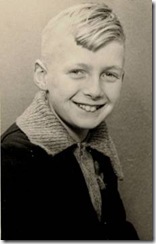

When I did my weekly collection with my order book and a leather satchel to put the money in, I would sometimes take Mark with me for the ride, and he would stand by my side as I talked to my customers. Mostly they were working class people who were as poor as church mice, but many of them would have something for the little blond haired boy standing at my side. Often in was a toffee or a biscuit, but sometimes he would get a silver three penny piece, or even now and again a sixpence. They were lovely people, the sort you would describe as: ‘The Salt of the Earth.’ Neither was it all one sided, I returned their kindness where and when I could. At one house the door was answered by a little old lady, who took a bottle of plain milk every second day. When I said I had called for the milk money she said in a very distressed state that she did not have any money, so would I be kind enough to wait for a few days until she got her pension. The amount was very small just a shilling or so, so I agreed to leave it till the following week, then she said don’t leave me any milk until I can pay in the meantime, and I told her that I would not see her with no milk for her tea. Bring me a jug and I will fill it for you I said, and I did this every second day until she could afford to buy a bottle of her own. (I have to confess that this milk did not cost me anything, because the company allowed for spillages, if a part empty bottle was returned they wrote it off as a job loss.) This pale old lady needed some nourishment so I gave her the best Devonshire double cream with the gold cap, and the following week when she still had no money I cancelled her debt; paying the small amount out of my own pocket; though she never knew that I could not cancel owed but had paid it for her.

All was going well; we had some money coming in so we would have a little to spend on the voyage which would now be more like a holiday. It always seems to be that when your luck is running for you good things happen one after another. So with a difficult job improving I was suddenly offered a promotion of sorts, though perhaps it should be described as a move sideways. The manager of the wholesale department came to me one day and said he had noticed that I had a heavy vehicle licence, so would I consider driving for him; there would be an increase in pay he told me. I agreed to do it and he told me that the next day I would be delivering wholesale to shops and supermarkets using a large articulated truck that would take a load of several tons of crated milk. This was going to be really exciting; I had the licence but had only driven a truck a few times on the Military Police driving course and that was several years ago now.

The next day I found an old man waiting for me who had been given the job of showing me the route and the points of delivery. I soon found that this was not going to be a pushover job, though the driving part was not a problem. It did not take me long to get the feel of this truck which though large, had a high cab with a wonderful all round view. It was powerful and I went rattling down the road at a fast clip with me enjoying every minute of it, until I came to the first corner which I took as though driving an ordinary car. My hair almost stood up straight on my head when I looked out my rear view mirror and saw my enormous load of milk crates leaning over at a considerable angle. For a split second I envisioned the whole lot smashed across the road, with a lake of milk all over the place, but I am glad to say my luck held good and the load rocked back again and stayed in place. Looking across at the old man who was supposed to be showing me the ropes I had to laugh at the look on his face; he was sitting with a look of frozen horror, and he was clearly not breathing.

It took the old man some time to recover his composure, but with me doing all the work all he had to do was sit in the cab and smoke one rather shaky cigarette after another. I had this rather useless companion for two or three days, then I was flying solo. The main problem with this job was the size and shape of the load I was carrying, the tray of the truck was at chest height, and the crates of milk were stacked at least six high, which was just about as high as I could reach. They were slotted into each other and to remove a crate from the top it was necessary to tilt the crate then jump it out of the top rim of the next crate down then lower it down until you had it in your hands. This procedure took some practice, and for the first week I had crates of milk crashing into my chest; when I went to bed at night I discovered that my chest was covered in large bruises, but eventually I got the technique right and the bruises disappeared. I have to say that though this job was physically demanding it was a better job that delivering door to door on a retail round.

Given the choice I opted to stay with this job until the day I left, though the retail manager did try and get me back. There was a big row about it one day when I went into the office for some orders, the retail manager saw me and he came marching up to me and the wholesale manager and began to shout about having his staff stolen from him without any prior consultation. So with me standing there they fought like two dogs with one bone, the upshot being that the senior manager won the day, arguing that although the retail man had employed me, I was much more valuable to the company driving a wholesale truck because drivers with a heavy goods licence were few and far between, whereas they could get plenty of retail drivers who only needed an ordinary driving licence.

At the time of the argument they did not notice I had a big smile on my face, I suppose they were much too busy shouting at each other. It must have come as quite a shock a week or two later when I announced my intention of leaving, at which time I confessed that I had taken the job only as a temporary measure, and had only been awaiting the sailing date of a ship. The manager said that he had thought there was more to me than met the eye, and was sorry to lose me. If I returned he said I could have my job back, he would also include a rise in pay to make the offer more attractive.