VOLUME 1 – CHAPTER 3 – Part 1

My father had heard about a soldier’s life, it was part of his family background; he had thought often of joining the ranks when he was old enough. Life seemed to have very little to offer at this point and he may have thought that the army might provide better prospects? The problem was that the minimum recruiting age was seventeen and six months, and so he was still too young by a year. If only he had been old enough the opportunity was available, the army had reduced to something like it's old pre-war numbers, and they were now all regulars with a professional approach to a soldiers trade. Life in a regular peacetime force was said to be well worthwhile, and the army was looking for suitable recruits. It would be a life that was organised and adventurous, and though there was no war to fight, there was still plenty of action awaiting the soldiers of the British Army

It seems strange to think that only a few months after the largest war the world had ever known had ended, the British Army was short of men. Just about all who had served in the war wanted out, but there were still troubled places in the Empire. And one that had recently erupted into full scale conflict was Ireland with the Irish rebellion erupting yet again. The recruiting offices had hardly shut their doors when they were back in business again, looking for yet more cannon fodder, and thanks to the downturn of the world economy, and the rise in unemployment, there were plenty of willing recruits such as my father.

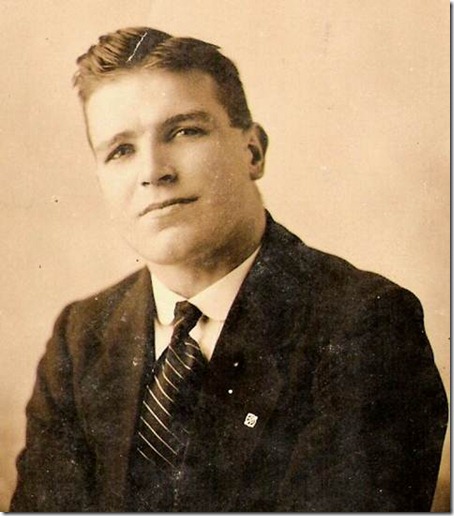

How did a boy of sixteen with the face of a cherub manage to talk his way into the army? Maybe the army was prepared to take just about anyone without asking too many questions, and possibly his Grandmother aided and abetted him. It is impossible to say, but the fact is that young Billy succeeded in deceiving the recruiting office in Bethesda Street in Hanley and took the Kings Shilling. Now he was Private Bishop of the 1st battalion, North Staffordshire Infantry Regiment.

After 27 years service in the army, with most of those years spent in his county regiment, my father and our family in general had reason to feel we belonged to it. I also spent a brief period in the regiment, - but that comes later in my story. - With this feeling in mind, it seems appropriate to outline some of the regiment’s history. It came into being in 1705 and in 1751 it became known as the Staffordshire Regiment and was designated the 38th of foot. In 1756 a second regiment was formed becoming the 64th of foot. Looking at the history of the regiment I have often wondered why it did not attract more attention from the public than it did. So much has been written about other units of the British Army, and so many of these units have become legendry. The record of the Staffordshire Regiment is second to none, so is it any wonder that this question has puzzled me. I once read that probably the most courageous and outstanding engagement ever fought by any unit in any army, was the breaching of the Hindenburg Line in 1918, and this operation was carried out by the North Midlands Territorial Division , and it was the North Stafford’s that spearheaded the attack. This action alone should have made them the most famous regiment in the British Army, but it does not seem to have done so.

By the time my father joined the regiment in 1920 the North Stafford’s had become The Prince of Wales’s North Staffordshire Regiment, and of course since 1870 part of the regiment had become the South Staffordshire Regiment. When the Second World War began more units were formed, and it was at this point that my father was propelled upwards and onwards. He became a commissioned officer and his first duty was to form a new unit; eventually he was reassigned to a special unit, which was designed for rapid re-supply of the forward troops. - I joined the 1st Battalion in 1950, and was with them when they were went to Trieste as part of a force sent to defend that important port from the threat of take-over by Marshal Tito, and his communist forces; but again I am anticipating later events in my story.

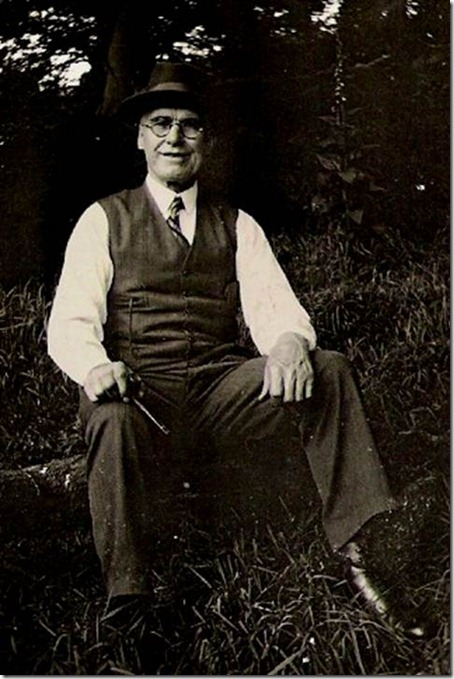

It was always difficult to get my father to talk about himself, and especially when it came to his years in the army. Looking back to the time when he joined up, it is not necessary for him to tell us that he would have gone to the regimental depot to do his basic training, and that the first few months may not have been very enjoyable. The one circumstance that might have alleviated the trauma of adjusting to army life, was probably the fact that he was based close enough to home to get week-end leave, which would have allowed him to go home and see Harriet his Grandmother. - I am sure this must have been the case because I also followed the same path, and exactly the same circumstances applied to me though some thirty years later. - The only mention of those early months was a reference to an early leave during which he decided to go and seek out his older sister Anne. Dad was to always keep in touch with his sister, though they would not see each other very often during the very different lives that they led.

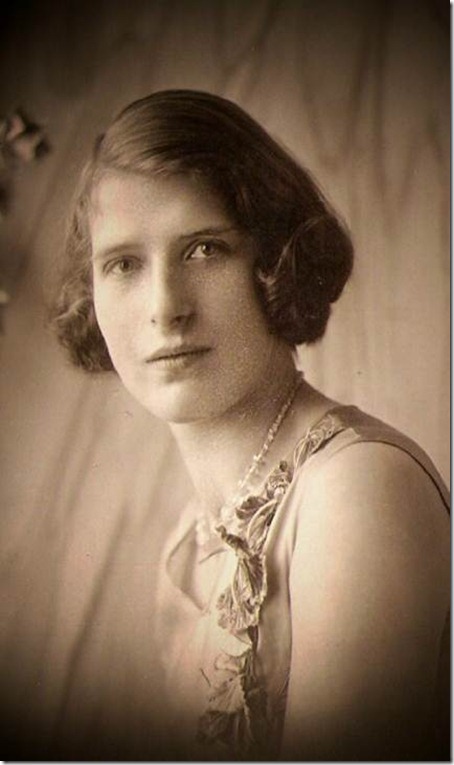

Aunt Anne was a remarkable woman with the same determined sort of personality my father had. She was to achieve a much higher level of education than most other young woman of her generation and she put it to good use. Compared with her brother her life was to prove much more satisfactory, she was to enjoy many advantages which a superior position in society was to provide. She married well and enjoyed a life which my father could only envy from a distance. An intelligent woman she always knew the reality of the situation, and never attempted to change the differences that kept her apart from her brother and her father’s other family. This may have been the case, but that does not mean that she rejected her brother; in fact she always insisted that he visit her and she him over the years, and they always had a strong affection for each other. However, their very different lives allowed few opportunities for a close relationship, and it is sad to say that they met very rarely.

It is certainly interesting to note that on the occasion when my father went to see his sister shortly after joining the army, her greeting had not been a very approving one. Many years after the event he was to tell me with more than a little chagrin that when Anne had opened the door to him and seen him standing there in uniform, her first words had been : "You silly fool, can't you find anything better to do with your life than join the army ?" To many, joining the army appears to suggest that the person concerned had failed to make the grade in civilian life, (Unless of course one is in a position to join the ranks as an officer and a gentleman; though sometimes even then the person concerned is thought to have opted for a military career as a last resort.) There is little doubt in my mind that my father was one of those who, finding life almost impossible, had taken refuge in the protecting but stifling folds of army life. His half-brother Albert was also to find himself in much the same sort of circumstances, and followed his half brother into the army. These facts as I outline them are not intended as a criticism, I am simply relating events as I believe them to be.

Bearing in mind that this is actually my story, I suppose this would be an appropriate place to record that this was to be my fate as well. The one major difference between my father, Uncle Albert, and myself, was that they were to be fortunate enough to make some success out of such a life ; a military career may have had very limited prospects for many, but in their case it did prove beneficial. In my case fate was to be far from kind, but that comes later in this story of mine.

After a period of training but as yet still a raw young recruit, young Bill joined a draft which was destined for the battalion in Ireland. This was more like it, the training over and only adventure ahead; this is what a young lad might have thought, though he was soon to find out that it was not going to be much fun. Landing at Belfast the reinforcements had a long march to their first destination; Dad recalled that even for a fit and healthy young man it was a long, hard, and exhausting march. It was winter and very cold and wet, and this experience was to be a traumatic one which remained for ever etched in his memory. He recalled that on reaching their destination and being allocated a billet, all the men wanted to do was sleep. “I was so tired I didn't even take off my great coat and all the equipment I was weighed down with, I just staggered to my bed and fell upon it. When I did the thing collapsed in a heap of iron and springs on the floor, but I was just too far gone to care, I just lay in the middle of the heap and slept." It was a cruel trick that the old hands had played on the youngest recruit who was so obviously finding it hard to cope. Typical of course, they were hard and without much sympathy, it was the sort of cruel humour that one might expect from such men in such a place and at such a time.

Looking back there seems to be nothing that one can say in favour of the attitudes and behaviour of the men with which my father was serving, but then one has to take into account what life was like in those days. Such treatment of a young lad seems today to be brutal and uncaring, but looking more deeply maybe it did serve a purpose. It would have certainly made the person involved more determined to fend for himself, and it was yet another way in which that individual could be tested. How young Bill behaved under such trying circumstances would decide how he might fit in, and fitting in was perhaps the most important skill of all for those who would be part of such a close knit society.

Listening to stories about Ireland in the 1920's it was my impression that often they did not equate with the official history of events at that time. There are a number of sources of information about such events; there is of course the news media and then there are official records. Additionally there are occasional individual accounts, and how varied these different accounts can be. Often it seems we find them at odds with the official records, when we take the trouble to investigate. A distortion is not always intended of course; it might have been that the issues involved were just too complex to be clearly understood, or possibly the writer lacked sufficient detail, and so resorted to stretching the truth. Reporting an event is not an easy task, difficult enough if attempted by an eye witness, but infinitely more so when based on the experiences and descriptions of others. Let it also be said that it is only human nature that we should colour events, and try to portray them as we wish them to appear; few of us have no axe to grind as a rule it seems.

Looking at events in Ireland during the period 1920/1921 through the eyes of a young recruit, one gets the impression that there was no real animosity between the soldiers of the British Army and the Irish people. One might even go so far as to say that even the Republicans, and the IRA which had come into being in 1919, did not consider that their fight was with the men in khaki. The powers that be might have a different view, but down at the intimate level where ordinary individuals faced each other, there seemed to be almost a reluctance to cause hurt to the ordinary man. Such an impression does not sit well with the official record of the events of the time, but maybe some factors have been ignored, or maybe not given credence. For example, many of the men on both sides had been comrades not long before, fighting and dying together in the mud of France and Belgium. It is surely hard to believe that they would now so lightly cast aside those bonds of comradeship and set about destroying each other.

Duty is deeply ingrained in soldiers with the intention of making them obedient to orders. Once this is achieved they can be depended on to carry out orders in every situation. In Ireland however, I believe the Irish and the British soldiers often tried to avoid actual confrontation. I have heard it said that the only time a degree of ruthlessness was revealed, on either side, was where the Black and Tans were involved in the conflict. An examination of the history of this force of paramilitary police might explain why this was so. However, now is not the time to examine this particular subject, though it does have a bearing on this story? What I wish to stress is the fact that whatever the degree of hatred and opposition between the Republicans and the British Army, it is a fact that some level of magnanimity must have existed between the two sides. If this had not been the case this narrative would never have been written, because my father would have been dead and I would not have existed at all.

Shortly after arriving in Ireland new recruits were allowed some freedom; though it appears that more care might have been taken to ensure that they understood enough about the local conditions to ensure safety. Young Billy with the boyish countenance and innocent expression found himself plodding along a country road, and he felt fortunate when some fellows in fancy looking uniforms stopped their truck to offer him a lift. In spite of the black caps and police type jackets, and the tan coloured jodhpurs, it is possible that my father did not know that these men were members of the previously mentioned Black and Tans. Had he known and realized how unpopular they were, he might have had enough sense to refuse their offer of a lift. However, the fact is he jumped in the back of the lorry and settled down to enjoy the ride, though it was not to be a long one. Not far away the Irish rebels, who were now calling themselves the Irish Republican Army, had set an ambush for this very vehicle that had picked up my father. The site of the trap was carefully chosen, it was on a sharp bend where the road had deep ditches on both sides. When the lorry rounded the bend the driver found himself confronted by a barrier with a group of armed men behind it.

Everything seemed to happen at once, the men at the barrier began to shoot and the vehicle skidded to a halt, those in the back instantly leaping out. Danger is a wonderful stimulant to the human mind, and in a flash my father thought to himself that this was his baptism of fire. He must have also wondered whether it might not only be his first but also his last such experience. He did not have time to feel frightened but he knew he had to get away or share the fate of the other passengers. Following his instincts her took to his heels running back down the road towards the sharp bend. It was then that he discovered that these IRA men were not new to this game, and they had occupied the ditch on the bend so that they could fire up the road towards the back of the ambushed lorry.

Quite clearly in his memory Dad has a vivid picture of the rifles pointing at him as he ran towards them. It must have taken him a minute or two to cover the distance to the bend, and he must have been very close when he followed the road round the corner in front of the waiting marksmen. He will never know why they did not kill him as they so obviously could have done. Was it because he was in khaki and just a young lad with whom they felt they had no quarrel? Was it sympathy for a young boy who looked too innocent to die, and was so clearly without any understanding of what he was doing or why he was there? We shall never know, but what we do know is that those Irishmen held their fire until the scared youngster had got clear of the guns, and then they continued with the business of ambushing the truck.

Looking back my father often wonders why he did not have the sense to dive into the ditch at the side of the road, but then it is always easy to be wise after the event. He also admits that from that moment onwards he was never able to feel any antagonism for the Irish. Fortunately he was never ordered into action against them, and admits that he was relieved that he was never called upon to oppose or harm them. Over the years that he was in the army he was to meet and make friends with many Irishmen. It is possible that some of them were to benefit from the good will that my father felt towards them as a result of the above incident.

Life in the army, in any army, is not a bed of roses, so we can say without doubt that pleasure and good times would have been in short supply for a young fellow like my father. On the other hand one has to say that his early years must have been good training, for the hard knocks and the physical pressures that army life offers. He was good soldier material; he had courage, and a stubborn nature. Generally speaking, he liked the life, though he did once admit to me that he found the discipline and lack of fairness hard to live with. This had led him to consider leaving the army in those early days. There were very few rights and entitlements in the army, but one of them was the right to buy yourself out if you felt so inclined. This sounds all very democratic but as you might expect the British Army was not at all keen on having its soldiers take advantage of such a scheme. To make it difficult they always took plenty of time considering such a request, and they did all they could to change the persons mind. They also made it a very expensive knowing that few would be able to find enough money to pay the considerable cost. In my father’s day a private soldier earned only a few shillings a week, so when you consider that it was about one hundred pounds to buy your freedom, it can be seen that the financial aspect was the one that prevented most from taking this step. It was this high cost that led to a well known army expression delivered by an imaginary young recruit writing home to his mother and saying: “Dear Mum, sell the pig and buy me out." To which the fictitious mother replied: “Dear Son, the pig is dead, soldier on."

Once over the difficult early days my father began to adjust, he soon began to realize that if one toed the line and kept ones nose clean, then the army could be almost tolerable. He also enjoyed periods of leave and it was a great feeling to arrive home with money in his pocket and no worries about the future. He felt he had escaped the depression and the spectre of unemployment; it certainly boosted his confidence knowing that he had the army to take care of him. When he visited his friends he could not help making comparisons and it became more apparent each time he saw them that as his life improved theirs got worse.

Unemployment was massive and increasing, and life for most people was grim and not made any easier by the country wide strikes that became a permanent part of daily living. The more my father saw of civilian life the more convinced he became that he was better off where he was. This feeling was reinforced by some of the things that happened to his unit on returning to England. For quite a period the army found itself providing guards for all sorts of industrial premises, and they were also to become a strike breaking work force when the authorities thought it necessary. In particular Dad remembers the battalion guarding Liverpool Docks, and also acting as dock workers loading and unloading ships in the port. The 1920's and 1930's will always be remembered as the period of 'The Great Strike' and there is no doubt that such bitter memories will never be forgotten. Those tragic times have burnt scars into the memories of the people, and those responsible must for ever bear the guilt for having let it happen.

It may have taken quite a time, but gradually the army became like a family to those who could adjust and get used to its ways. It provided a feeling of security and a feeling of belonging, something which had been missing in my father’s formative years. There was also adventure and comradeship and opportunities to see places and do things that would have been undreamt of in the ordinary way. So this was to be the future for Bill Bishop, and he was also to discover that the longer one held to this specialized life the more difficult it became to think of returning to the life of a civilian.

I have never heard my father talk about a sense of achievement, though I am sure he must have felt he was successful. Slowly but surely he demonstrated his worth, promotion came, a reward for his hard work and determined effort. If it is meant to be it will happen; life is a lottery, as we all know. A military life especially has its risks, and there were times when it could have all come to an abrupt end.

Early in the 1920's the battalion was sent on garrison duty to Gibraltar, not a bad posting they mostly thought. A sunny climate and some experience of foreign parts. Not too many duties to perform, and plenty of time to relax, and swim in the warm blue waters around 'The Rock'. It was this fondness for swimming that led to one of the occasions when young Billy's career nearly came to a premature end. Perhaps it was the fact that he had never lived near the coast and had little practice as a swimmer, but the fact is he was not very good at it. Good enough he had thought to accept the challenge of swimming as far out as the other more experienced swimmers did. - For young men the motto is never admit you are scared or can't do it. - Being new arrivals our young Staffordshire lads were not aware that the straits between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic were subject to very powerful tides and currents. They were to discover later that more than one young fellow had lost his life in the waters around Gibraltar.

The swimming party were having a grand time, and Billy found the clear water so refreshing after the hot barracks. He did not notice that for an inexperienced swimmer using the breast stroke he seemed to be making very rapid progress as he swam out from the shore. Eventually he decided he was perhaps a little too far away from his pals and turned back. Gradually he began to realise that maybe he was in trouble, try as he might he could not make any impression on the distance between himself and safety. It was quite a while before he was once more safe on the shore, and during that time, which had seemed a lifetime, he had swum to the point of exhaustion. Nearing the end of his tether, and feeling completely exhausted, he had accepted the ghastly thought that he was going to drown.

Being young and fit undoubtedly contributed to his survival, but he would never have made it on his own. As luck would have it, and fortunately for him, there were other men in the swimming party both older, wiser, and much better swimmers. It is possible that the more senior ranks in the party knew that they would be in big trouble if one of the younger men had drowned. Anyway, he was a comrade, and a soldier risks his life for his brothers, they were not going to leave him to drown. When the other men saw he was in trouble, several of my father’s comrades went to his aid, swimming out to where he was struggling and gradually towing and escorting him back to dry land. Dame fortune had smiled on him, as she had done in Ireland, and was to continue smiling for some time to come. It must have been a nice change for someone who had been so lacking in good fortune in his early years.

It is with some emotion that I write of my father’s near drowning, because I had a similar experience when I was in the army some thirty odd years later. How he must have felt at that fateful moment comes readily to my mind. When I write about it my own memories come flooding back; such dramatic events are so vivid they are never forgotten.