Volume 1 – Chapter 8 –Part 1

Returning to England meant returning to the regimental depot at Whittington, a small village a short distance away from the barracks. A military establishment is a world within a world, and quite isolated. The nearest town was Lichfield, about 2/3 miles to the North, and the other garrison town was Tamworth, which was roughly 6/7 miles to the South. Apart from the occasional bus and private car passing by, transport was not readily available, so there was little reason for military personnel to leave the confines of the camp. The lack of built up areas and population made this location ideal for such an establishment, and being self contained there was little reason for the outside world to intrude. In fact it could be said that life in an arm y camp is rather like being in a benevolent prison; it was more tolerable for the none serving personnel of course - Those once called Camp Followers - , though families were just as strictly controlled with as many rules and regulations as the men in uniform.

Those in a position of authority did not suffer of course; after all, it was their world and their rules. If anything they may even have derived some pleasure out of inflicting discomfort on those under their control, undoubtedly there were some who enjoyed making life difficult for others. - It is interesting to see how often a streak of cruelty appears in people who are given power over others. - The life of military personnel and their families is institutionalized and totally divorced from the usual rules of civilian life. It is inevitable therefore, that rules and discipline should be taken to the extreme. A military life can be a transient sort of existence, soldiers come and they go, they can never say they will be here today or gone tomorrow. It is a rootless sort of life, which more often than not, results in feelings of uncertainty and instability. Under such conditions, the presence of a family can bring comfort to a serving man, which is why the army allows the presence of women and children in their establishments. It might help the enlisted man but this does not mean that such a life is beneficial for the families. Conditions may be different in this present day and age, in the past families were deprived of many of the opportunities available to those in civilian life.

For anyone with confidence in the future, with prospects, and a desire to be independent, a life in an army environment would be unacceptable. On the other hand, the very aspects of such a life that makes it objectionable to some make it appear desirable to others. Job security meant freedom from the spectre of unemployment. The fact that every need is taken care of, and you are cared for. These factors attract many to a life in the army. Maybe this is why it often becomes a tradition with so many families, who follow it over generations. The trouble is that there is a negative side to it, and that is the narrowing of horizons and the absence of opportunities, unless you have the benefit of the class structure, which is so much part of military life for the British.

Perhaps at this crossroads in his life my father should have left the army, but he did not. He still had prospects, and much to lose by leaving. Even though the advantages of a life in India had been taken from him, he still had a couple of years to go before his period of service was up. Therefore, as the saying goes, we were to ‘Soldier On.’ Events now took control of our lives, the next time that my father was to face this decision was in 1946, and this time he decided to leave. Looking back I have to say that on both occasions my father’s decisions were not to my advantage, and it seems they may not have been to his advantage either.

The army's motto -’yours is not to reason why' - was and still is applied to not only the recruits, but to their families as well. We had returned to England to what seemed to be a very different world. The military machine is an unfeeling entity, a fact that should not surprise us. What is surprising is how often it also seems devoid of rational thought. If intelligent thought was applied more often, it would have resulted in the realisation that happy well-adjusted cogs in the military machine would surely perform more efficiently. Care, courtesy, consideration, and all the other needs that make successful and useful human beings were sadly lacking from military life. The finer feelings of people are of no concern to the army. To imagine that the authorities would be the slightest bit interested in the effects of our move from India to a dreary and dismal barracks in England would be farcical. For a brief time in India, we had enjoyed a superior way of living, but that was a different world, and now we were had returned to the life we came from.

The long established attitude still existed, that officers are gentlemen, and other ranks hardly more than the dregs of society. I am sure that these words would be disputed by some, but the facts speak for themselves. Officers received every consideration, whereas very little was done for other ranks and their families.

The reader will be aware that I describe these things in retrospect; today it is different. We question things more readily in today’s world, but until recent times the English had been conditioned to accept authority without question, especially in the army. Tradition is still a powerful influence, which is why so many accept without question. It was not done to question anything, and those that did were quickly branded as troublemakers.

From a child’s point of view life continued to be idyllic, and when I think back to those times I can recall many happy days of freedom. For me there were no thoughts of the future, children do not consider such things. The grownups and those who plan, they should be looking ahead. In my case, I could be forgiven for concluding that my parents did very little thinking ahead. What were our needs, and where were we heading? It seems, for my parents, surviving from day to day was their only concern. My future was never a consideration; it seems they believed it would take care of itself. For two years or more, we lived in this vacuum, and though my father continued to make progress in his chosen career, for my mother and I time stood still. We became two years older, and that would be all I can say about the march of events. Whether my mother worried about such things I will never know, but for me it would be a long time before I would become concerned about the future.

For my mother the loss of the superior life style we had in India was no sacrifice, in spite of our reduced circumstances. For her just returning to England was an improvement. The next step would be to escape from life in a military establishment. I am not able to say what my mother wanted exactly, but it would be logical to assume that she hoped to return to the comfort and safety of friends and family. I doubt that she expected to find herself confined to the stultifying life she now faced at Whittington Barracks, but at least she was close enough to family to be able to visit.

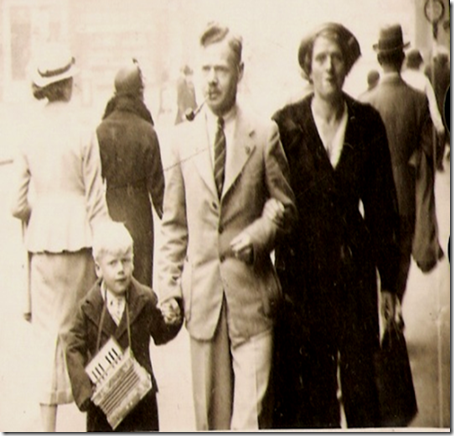

Occasionally we were able to make a brief escape from army life. In this picture we were on a holiday to Blackpool. I was at this time about 4½ years old, but already my liking for music had made itself apparent.

As newcomers, we were allotted the older and less desirable married quarters for the first few months. We were among strangers, the people we knew and those we had become friendly with were still in India with the Battalion. Of course, my father knew some of the depot staff, and many knew him by name and reputation. This was my father’s world; he had his work and the security of his rank and position. For my mother and me it was a different scene, for Mary it was still a strange and alien world. We had no friends, and my mother’s retiring personality did not help the situation; also, I suspect that her standards and values proved to be a barrier. Many of the women in married quarters were from what could be described as dubious origins. Some were foreigners who had married men serving in the battalion during its postings in different parts of the world; some were little better than servants, who carried out the function of a wife in return for a better life.

It was not long before my father had found his niche, and begun to win approval from those in authority. He was seen by many to be an old hand, a professional who knew the ropes. Many of the officers found themselves leaving matters in his capable hands. - One such young subaltern was a lieutenant Radford, who, as a lieutenant colonel, in 1950, became my commanding officer when I joined the battalion. - This of course was nothing new; it is well known that NCOs run the British Army and officers of commissioned rank take it for granted that a good NCO shoulders the main burden of work, thereby making the officers life more agreeable.

In addition to his work expertise, father now had additional means of furthering his career. He had the social and sporting skills, developed during his service in India. He wasted no time in putting them to good use, though it was soon apparent that a return to England had not changed my mother’s attitude. When providing a general description of events from a distance, it is difficult not to give a misleading impression. I am sure my father was sensitive to his wife’s feelings, but inevitably he was not about to let them stand in his way. It was clear what he had to do, and anyway he enjoyed the social life and the sport. It is easy to take the view that my mother was a victim of her husband’s unfeeling and insensitive behaviour; however, it is necessary to take into account the character and temperament of the man. Consider my father’s history, and allow for the time and the place? Maybe we should have some sympathy for him, and the problems his over sensitive and unsophisticated wife had caused him. My father had worked hard to get to his present position, and he was not going to give it up easily. He may have reasoned that it was his wife’s duty to do everything she could to support him; and to a military mind the greatest sin was to fail in ones duty.

At the time I knew nothing of the things that were shaping our lives, but in later years I began to puzzle over what had happened and why. Now as I write I attempt to explain it all, and understand. I have never discussed these events with my father, but if I could have done so, I am sure he would have said that he did what he thought was right at the time. It is very easy to be wise in retrospect, so I shall try not to judge the actions taken, I shall just write what I can remember. Looking back it is not difficult to see that Mary had not been suited to the life she was being asked to lead, and that if these proceedings had taken place in a more modern setting, it is likely that my parents would have parted company. Looking at their relationship through my mother’s eyes, it would be my surmise that she would have seen herself as living under the control of another despot, such as her father had been. My father was a good man with many admirable qualities, and it must be said that he always did his duty as he saw it. He was at the same time a product of his times, and it is doubtful that the march of events could have taken a different course. If my father was here to comment, I am sure he would say that he had not understood his wife, and so behaved in an insensitive manner. However, the fault was not all his and Mary had to accept her share of the blame for a marriage, which was not always a happy one. If my mother had difficulties coping with life, they originated long before she became a married woman. The root causes can be traced back to her childhood, her inherited qualities, and her personality. In later life, she continued to develop, and mature, but much of her character would never change.

To explain how my life was to unfold it is necessary to describe how my parent’s lives were progressing. After so many years, it is to be expected that my memories would be vague to say the least, so to a large degree I must leave it to the perceptive reader to imagine the scene, and to understand the characters I describe. As a child, I might not have been conscious of the conditions under which I was living, but more mature minds would recognize that the situation I describe would have had a disturbing influence on me. The constantly changing environment resulted in an atmosphere of insecurity. These conditions may have also contributed to the lack of motivation and parental guidance displayed by my parents, it could be said that my parents were preoccupied with their own problems, which blinded them to the needs of their child. Nevertheless, I recognise that this is purely conjecture on my part. Assuming that I am right, then it might also be said that had the situation been only temporary then all may not have been lost. No matter how one looks at the turn of events, the fact is that my prospects continued to be poor, and my development, especially in the matter of education and all forms of learning continued to languish.

The instability of the way we lived taught me to rely on my own resources, and to be content with my own company. You could say that my survival instincts became well developed. In the barracks where I now resided I found myself in the proximity of quite a number of other children who were living the same sort of insecure life. I was quiet and not inclined to be sociable, and this gave an impression of timidity, though timid I certainly was not. Usually I was not a difficult child, and more often than not happy to cooperate with those around me. However, my benevolent nature did not save me from trouble. Human nature being what it is my inoffensive demeanour often resulted in aggression from others, who saw in me as an easy target. It is natural for people, and especially children, to instinctively look for weaknesses in others which might allow them to improve their place in the pecking order. - I was to find that life within the enclosed world of Whittington Barracks was very much like being with that tribe of children on an island in the story ‘Lord of the Flies‘. - The inoffensive and innocent seem to attract predatory types, who are drawn like wasps to a honey pot?

There appeared to be no school for these army brats, and being free to wander without supervision they had plenty of time to get into mischief. Some of these children joined and became a gang, who, like the ‘Gasworks Gang’ in the ‘Beano’ or the ‘Dandy’, became an even greater menace than the other children that roamed in ones and twos. When I think of the time, which I now describe, my impression is of how insecure I felt; like a young animal in the jungle.

Man is a gregarious animal who tends to form social groups or packs, and of course, there is always much competition to establish a satisfactory position in the order of things. This is never more apparent than in the young, and so it is not surprising that I soon found myself at the mercy of the gang I have already mentioned. It was inevitable that I would become a target, I was young, alone, inoffensive, in their domain, and apparently unable to resist. There is nothing more tempting to the bully, - And there is a streak of bully in most of us, - than the sight of a victim who is clearly harmless, defenceless, and unable to escape their sadistic attentions.

It was about my sixth birthday when I first met my persecutors. I had been allowed to wander for some time but had always managed to avoid this group; I had seen them at a distance and recognized by pure instinct that they were likely to be a danger to me, but for a while, I had managed to avoid their clutches. There were one or two other children in quiet corners of the barracks with whom I had become friendly, and it was on an occasion when I was returning from a visit to one of these distant friends that I was careless enough to allow the gang to see me before I saw them. They must have felt very pleased with themselves when they realized that at last they had a prospective victim in their clutches. I was younger than the children in the gang and I believe that it annoyed them that someone so young could have outsmarted them until now.

Living with the military it was to be expected that the group had absorbed their ways, and so they quickly formed a squad around me and proceeded to march me off in the direction of the common. Most of the married quarters were along the outer edge of the barracks close to the perimeter wall. - To assist the reader in imagining the scene, let me describe the locality. The barracks with its brick and stone buildings stretched for maybe half a mile alongside the road from Litchfield to Tamworth, and its depth was almost as great. It had a high wall around it, and outside the wall was a large expanse of heath or common, which was used by the troops for training and exercises. - Once away from the public gaze, and safe from detection, I imagine they had something unpleasant in mind for me. Whatever they meant to do, I had no doubt that it was not going to be agreeable from my perspective.

Innocent and naive I might have been, but I had no doubt that this group of about 7 or 8 boys, aged from maybe 7 to 10 or 11 years of age, intended making my life a misery, and they were going to enjoy doing it. This was possibly the first time in my short existence that I had to show what I was made of. My only chance to avoid my fate depended on me remaining cool, thinking quickly, and acting before slower wits became aware of my intentions. - Later in life, I was to use this ability on a number of occasions. - I quickly realised that if they marched me away from the road, which ran around the barracks just inside the wall, my chances of escape would be greatly reduced. It was now or never so choosing my moment, I turned suddenly and looked back, waiving my arm as if signalling for help. Naturally, the group around me also turned to see who might be coming to my aid, and that gave me the chance I needed. The moment my enemies were distracted I took to my heels in the direction we had been marching. The two boys who had been in front of me had not seen me wave and so had not turned, and it was not until I was several yards in front of them and running like a frightened rabbit, that they reacted to my escape and gave chase. One of my pursuers was the leader of the gang who began to shout angry threats, and demands that I stop, but I was not about to do that.

The leader was not slow to realize that I was a very speedy customer, and seeing that he was not going to catch me, he resorted to one final measure in an effort to prevent my escape. In his hands, he was carrying a large wooden mallet, some sort of staff of office, or possibly an instrument with which he dominated and punished those around him. Having called on me to stop, and with the distance between us still only about ten or twelve feet, he let fly with the mallet hurling it as hard as he could. It was quite a heavy missile, but the thrower was not without some skill and proved to have a strong arm; at a distance of 15 or 20 paces, I was well within his range, and he hit me squarely in the middle of my back. The force of the blow made me stagger, and I almost fell, but I cannot recall feeling any pain. Realising now that I was going to escape, I lost my fear, and became angry. Without really thinking about it I turned, noted the tableau of frozen figures a short distance away, picked up the mallet, and after flourishing it defiantly in the air, I turned again and ran like the wind.

Some boys would have made the threat with the mallet but would have stopped short of throwing it; after all the thrower could not be sure where it might hit, and what degree of injury it would cause. One might also wonder whether the angry youth ever considered that, his intended victim was only a very small boy, who had done nothing to cause offence, so why risk serious injury to him? However, this fellow did not hesitate, he had not become leader of the gang by being a softie, and he was not going to be made to look like a fool of by some little pipsqueak. He had intended that I should feel his wrath, to suffer; such is the mentality of such despicable individuals, who go on to become men capable of cruelty and evil all their lives.

When this adventure was over, I remember feeling quite a thrill at the thought that I had outwitted the 'Mallet Gang'; the name I mentally gave this bunch of thugs. I was quite proud of myself, knowing that I had controlled my fear in the face of what to me had been a very dangerous situation. This euphoria did not last long, I quickly realised that from this moment on I would a marked man. I knew that I had been lucky, and for a couple of weeks I stayed close to home. Eventually, as my fear subsided, I ventured further and further afield, but always like a hunted fox, with my wits well and truly sharpened in case of danger. With the passing of time, it seemed the gang had lost interest in me, or so I thought, until one day they spotted me once again and gave chase with great determination. I remained elusive, but began to feel quite sorry for myself; after all, it seemed so unfair. I had done nothing to deserve such persistent persecution; it seemed that I had become something of a hobby and a way of passing the time for the gang. For some unaccountable reason my defiance, and my ability to outwit them, had become a permanent irritation. Branded into their collective consciousness was a desire for revenge. Until they had achieved it, I would remain uppermost in their minds. Of course, it might have been that they wanted their mallet back.

I had a number of encounters with my enemies, and on one further occasion, they came very close to catching me. Again, I was to show, - to use a modern day expression, - that I was street smart. Looking back, I have to smile when I think just how resourceful I proved to be; I was young and had little experience of the world and its cruelties, but as the saying goes, ' Needs must when the Devil drives.' I was learning quickly and there is no doubt that I continued to elude my persecutors because the constant atmosphere of danger had sharpened my wits. I was becoming a loner and careful, I was also a thinker and a planner, and I now decided to prepare for the day when I might find myself in yet another difficult situation. It became almost a second nature to keep in mind where I was at all times, and to always remember that I should have an escape route available to me if my enemies appeared. This attitude was to prove my salvation on another day of high drama and excitement when the ‘Mallet Gang’ nearly seized their quarry.

I suppose to the gang their persecution of one little boy was just a bit of sport, a way of amusing themselves. I am not even sure that it was always the same boys, but if the members of the gang changed from time to time, I know for sure that the leader was always that same vindictive individual. On the day in question I had allowed my caution to abate a little, I had made friends with two children who were new to me. They were well dressed and polite and I seem to remember that they told me that their father was an officer at the barracks, and that they were spending their holidays with him before returning to the public schools that they attended. We had made friends and I quickly became their guide and companion, a mine of information about where to go and what to do on warm sunny summer days. A fact of minor importance, I had failed to mention, it was summer time and we were in our short sleeves and sandals.

The high brick wall around the barracks, that I have already mentioned, had several entrances and exits, one of them being near to the married quarters. It had been my habit to slip out of this particular gateway onto the common. What a wonderful place for a boy to find adventure and solitude. Naturally, I had taken my new friends in this direction. This open heath was not only ideal for children's adventures, it was also a training area for the recruits at the depot, and because of this training, there were a number of trenches not far from the barracks wall. One of these trenches was a favourite of mine; I could not say how long it was, but it took quite a time to walk through it, and I would guess that it must have twisted and meandered its way for quite a few hundred yards. However, an important feature that I should mention was that the two ends of the trench were only about 50 or 60 yards apart, and it was possible for someone standing by one entrance to see the other. It had corners and bends in a very complex layout, and for me it was great fun to venture into it and explore, though I was aware of the fact that being about 7 or 8 feet deep it could become a trap, being far too deep for children, and even many adults, to climb out, without some assistance.

It was in this locality that I now found myself with my new friends; we set out to explore and enjoy any adventures that the day may hold for us. Now however, to my dismay I became aware of the fact that the dreaded ‘Mallet Gang’ had found me once again. I also realised in an instant that they must have been on my trail for some time, as they had already spread themselves into a formation designed to cut me off from any escape in the direction of the barracks. Retreat was impossible and I knew that though I might outrun them for a while, sooner or later they would use their numbers to close in and trap me. Danger certainly sharpens the senses, and once again my brain slipped into overdrive, as I considered my options and decided what I should do. Quickly I explained my dilemma to my companions; pointing out to them that there was nothing I could do but run, and assuring them that the gang would have no interest in them, and that they would be safe providing I had departed.

Having made my excuses I took to my heels and ran for the long trench which was not very far away, and as I bolted down one of its entrances I heard a yell of triumph from my pursuers, who now concluded that they had me in a trap. They all knew this trench and so were quite right to think that if they entered it from both ends they would come upon me somewhere along its length. I did not see them split into two groups but I knew that is what they would do, and though I had a plan I felt considerable trepidation as I dived out of sight into the trench. I was more than anxious as I dashed along, there were no by-ways or dug-outs in which I might hide, and I can honestly say that my heart was in my mouth.

I have no idea how long it took them to run the length of the trench, but I suppose it was several minutes later that the two groups of bully boys met somewhere near the half way point, and held a discussion on what had happened to their intended victim. How had I managed to vanish into thin air? It must have been most perplexing for them, not to mention frustrating, to have me get the better of them yet again. Looking back on this event later, I have to say that I felt considerable regret that I had not been able to witness their puzzlement.

How did I manage to disappear? The answer, like many such answers was simple, in fact at the time I was sure they would figure it out, and find me. With safety in mind, I had on a previous visit to this trench, discovered part way along its length, a place where it circled back on itself, running around a large bushy tree that provided cover down to the ground. At this point I had also noticed a piece of rock which protruded from the wall of the trench about two feet or so from the ground. The protrusion was only a couple of inches and insignificant enough to escape attention, but I had discovered that it was just enough to make it usable as a step. With the help of a small groove that I had carefully made in the hard sandy soil a little higher up, I had made it possible to climb the side of the trench and wriggle under the edge of the tree, becoming hidden from every direction. Beneath the branches there was plenty of space, and it was here that I had made myself a cosy den. One of a number of places I knew I could hide and find safety. You can imagine how I felt as I lay in hiding, with my heart in my mouth, wondering whether they would discover me. I heard one of the groups dash past, and knew that now they would look for an answer to my mysterious disappearance. It seemed ages before I could convince myself that they were not going to find me, and then of course I was filled with delight at the thought that I had outsmarted them yet again.

My troubles with these local boys must surely suggest that we were running wild, and I have to say that I am sure we were. How was it that we all appeared to have so much time to get into mischief? The answer to this question is probably not a simple one, but it seems fairly certain that a large part of the problem stemmed for the fact that there was no school at the barracks. We were not part of public life, and being isolated we were bereft of the facilities that society provide. I may be wrong, but in retrospect it appears that unless parents at the barracks were able to send their children to a public school, the children were left almost completely to their own devices. I am sure the army were supposed to provide for the education of children living in military quarters, and I have to say that before I departed from Whittington Barracks a class was formed. - or possibly it might have been classes, because I never saw some of the older children in the class I describe, - On the face of it our educational needs were to be catered for. In reality all that was achieved was a means of keeping some of us out of mischief. On the few occasions that I attended this class I cannot recall any formal tuition being provided. The young woman, who was given the responsibility of educating us, was in fact nothing more than a benevolent jailer. We drew pictures, and she read us stories, and we were told that if we were good and caused her no trouble, we would be allowed to go home early, so the hours we spent in class were often very short indeed. When I left Whittington Barracks I had not even begun to learn, and this lack of the basics was to dog me until I finally left the educational system in 1948. The education system we had in England was like a conveyor belt, and a child not on the belt from the beginning were never going to catch up. Maybe it is more akin to missing a train, those left on the platform are never going anywhere.

If one could say that I was learning anything, then it would have to be said that it was only the lessons that life was teaching me. The only tuition I was to get was in the school of ‘Hard Knocks’ and many of my class mates seemed intent on teaching me all there was to know on the subject. My nature was not a belligerent one, and all I wanted was to live and let live, but I was finding that trouble had a habit of looking for me, and that fight or flight was the only solution. I did not understand why life was like this, why was I so often like a fish out of water? Why did I never feel that I belonged? Why did my father ignore my plight? My head was full of whys, and no one was providing any answers. Had my mother been more settled, she would have been able to help me with my problems, but she was struggling herself. She was unhappy and I knew it, and I had already discovered that her answer to every problem was to walk away from it. We needed someone to help us both, and the only one we had was Dad, and he did not even recognise that we had any problems. If he had been aware of the problems we had, it is likely that he would have considered them, just part of everyday life. He had dealt with such difficulties himself, so surely we should do the same. To make matters worse our lives were shortly to be thrown into even greater turmoil, by the outbreak of the Second World War, but at this point in my story we did not know that.

Misfit or not I did in fact manage to make one or two friends at the barracks, and thinking of these things brings to my mind another quiet boy with whom I shared some adventures and some of my problems. His name was Peter Pugh and he was about a year older than me, though physically and mentally I was stronger and more mature. We did not spend very much time together, events soon separating us, but I can recall at least one incident which adds to the detail of what life was like for me at this time.

Peter and I got into trouble, and though we were clearly in the wrong, I have to say that at the time, and as far as I can recall, (and I am sure this would apply to Peter as well,) our actions were completely innocent. We had been exploring, once again on the common, and we had come across what looked like a large red barn. It was a dilapidated sort of place with considerable areas of windows made up of small panes of glass, most of which were broken. Being so run down with such an abandoned look, we assumed that it was no longer in use, and just another place where two young boys could play and indulge their natural destructive tendencies. Noticing that a few of the panes of glass were still intact, it occurred to us that it might be fun to demonstrate our skill by trying to hit them with pebbles which were handy nearby; there seemed no harm in the idea. Those few unbroken pieces of glass drew our attention like a magnet; it was the same sort of attraction that is often generated by the sight of an expanse of unmarked snow, which creates an urge in us, (especially little boys,) to mark it with a trail of footprints. If I am to be honest I would have to say that the idea was probably mine, as Peter really was a timid sort of soul, and it was only with my encouragement that he became willing to join in this escapade.

It was not my nature to break the rules, and had I known that the broken down building was in fact an old garage and workshop which was still required by the authorities, I would never have even considered the action I was about to take. This old building was in a very bad state of repair and it was only in the last few days that the army had decided to upgrade it, and having started the job they were not pleased when a large number of the windows had been smashed by persons unknown. - If I had been asked to guess who was responsible for the earlier damage, I would have said that it was probably my old enemies the 'Mallet Gang’, but this was not a question that ever came up. - What a shock it was to us when we let fly with our first salvo, because in an instant two young soldiers appeared as if by magic and we were apprehended.

We might have been innocent of any evil intent, but on the face of it we had been caught red handed, and I suppose we were assumed to be the perpetrators of the earlier damage. Perhaps it was because we were so young, that we were never questioned about the damage done, nor were we ever allowed to explain that it had never been our intention to perform a malicious or criminal act. The young soldiers who caught us were not about to reason with us, as far as they were concerned they had us fair and square. From our point of view the picture looked completely different, we were not aware that we were guilty of wrong doing, and this sudden attack by two men frightened us considerably. The way in which we reacted was interesting. One of the soldiers took Peter by the scruff of the neck, and being totally demoralized he began to cry offering no resistance; seeing that there was no fight in him he was treated kindly, being led by the hand on our journey to the guard room which was at the main gate of the barracks. On the other hand it was understandable that I should have imagined that we were being set on by a pair of thugs in uniform, and not knowing what their intentions were, I resisted fiercely giving my arrester no end of trouble. I yelled and shouted and threatened them with dire punishment for this attack, I was frightened but indignant and determined not to give in without a struggle. From the soldiers point of view I was of course not only a vandal but also it seemed a trouble maker, and so it was understandable when he decided to take firm measures to deal with me. This he did by picking me up like a sack of coal and throwing me over his shoulder. Held in a tight grip and in a very uncomfortable position I was carried off to the guard room in an undignified manner indeed.

This incident and the way in which I behaved must have been very embarrassing for my father, who, to his credit, came and rescued me and took me home without one word of recrimination. Knowing him as I do now, I often wonder why he neither questioned me about my apparent offence, nor punished me for what he must have considered a serious breach of discipline. So many of these events are unknown to me that I can only speculate, and on this occasion it would be my opinion that my father might have thought a visit to the guard room punishment enough for a small boy. Though he would not have known that once I reached the guard post and realized that I was not in any personal danger, I had soon calmed down and quickly became friends with the guards; who had, I’m sure, derived much amusement from my anger and belligerence, and had also, I suspect, approved of my grit and determination. In addition it must have helped my confidence no end when I was given a large mug of tea and treated as something of a hero; though I had no idea why.

The nature of man and human behaviour is an endlessly fascinating subject, though it is a most complicated thing to study; one’s own personality and behaviour being the most difficult of all to understand. One of the reasons I decided to write these memoirs was as a means of clarifying and attempting to explain why my life turned out the way it did. The more knowledgeable reader might at this juncture take issue with such objectives, considering them beyond the bounds of possibility, but even if in only a limited way, I have to say that I have learned enough about my life already from my writings, to have made the exercise worthwhile.

I have always seen myself as what is usually referred to as a square peg in a round hole, and though the reason for this is becoming clearer, it is certain that now, at the end of my life, I am not going to change. Being out of step and feeling that you have little in common with the people around you, that is not an unusual experience I know, but for me there has always been a strong compulsion find out why. Recalling the early days of my life I now see that my lack of social skills originate from those times, both the conditions and the circumstances contributed to making me what I was to become. Right from the beginning it was the instability and lack of continuity that created the social vacuum in which I developed. Had these conditions been of a temporary nature the outcome might not have been so extreme; though some effects would have been unavoidable. The lack of an education was also a major factor in my life, and this also will become more apparent as the story unfolds.

The human animal is extremely sensitive to the behaviour of its own kind, and our reactions are not always conscious ones. Without even thinking about it we constantly monitor and evaluate those around us, and I would say that sensing that others do not fit in is an instinctive thing. The question is why is it so important? Why on the one hand do we wish to fit in, and why on the other hand do the common herd try so hard to detect and reject the newcomer, or the misfit in their midst. This question of compatibility applies also to ones social position, and though in this present day and age the differences in social levels are said to be less marked, they do still exist. With reference to my father, whatever his problems, he continued to prove his worth in his chosen profession, he continued to climb through the ranks, to gain in prestige, and authority. But to the class ridden society that was the British Army, it would take a war to turn my father into an officer and a gentleman; the two being in their view one and the same thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment