Returning to our hometown was not a comforting experience for me, it was just another new and strange place; even for my mother it was not like returning home. For the first few month’s we rented a house in a suburb called Heron Cross, which was about a mile away from where I had been born at Fenton. We visited relatives of course, but most of the time domestic matters kept us at home, and I continued to live an isolated existence. It must have been a difficult time for my mother she was alone with two children, one being her new baby.

My mother would have done her best to occupy me, but she must have realised that I would need something more than just her company. It would have been about the time of my birthday when we moved, whether that was the reason I don’t know, but I remember she bought me a bicycle. It was small size suitable for a young child, and for the next few months I spent much of my time on this machine learning to ride. In her usual fashion, my mother gave me the bike and considered she had done her duty. I had no one to teach me, and I had to do it the hard way, on my own. Where we lived the road had a steep slope, and I can see the scene clearly, risking my neck in uncontrolled ventures, as I careered down the hill with my heart in my mouth. I seem to recall that the brakes on this little cycle were not very effective, and eventually, after we had moved to Fenton, I ran into a wall and the resulting damage was never repaired.

Adults never tell children what is going on, so I did not know how much the rent was on the house we were occupying. Neither did I know that we were waiting for a council house near to my Aunty Jin. And why shouldn’t we live in a council house? My Aunt and two of her brothers did, all in the Fenton area. Not that we visited them very often in those first few months I can only remember visiting one other family who lived a couple of streets away. This was Mrs Humphries, also an evacuee from the barracks at Whittington. Like my mother, Mrs Humphries was living with her children, two daughters. The oldest was Jean who was about my age. For a time Jean and her younger sister were my only playmates, though only when we visited, which was not very often. I do have a picture in my mind of a particular day that summer when the girls and I were allowed to play together. In a small field near their house, and we had made a tent with a clotheshorse and a blanket. What game did the girls want to play? Naturally, it was happy families, with Jean as mother, serving tea and all that sort of thing. My part in the game was the henpecked husband, who had to do what his wife ordered him to do. Little did I realise it at the time, but I was getting a demonstration of how grownups behaved.

All too soon our temporary existence came to an end, and I imagine that it was thanks to Aunty Jin’s efforts that a council house was allocated to us at number 93 Broad Street. This house was on a hill about 100 yards above the house in which I had been born. Three houses above us was number 99 where Aunty Jin lived. I am not sure just when we moved, but it must have been towards the end of 1940, or maybe it was early in 1941. What I can record is that we remained in this small two bed roomed terraced house until a larger council house was offered to us after the war had ended. So for the next six years I was to remain in one place, and like it or not I had to get used to it. This was to be the first time I was tied to one place for any length of time. I now realise that though there were many disadvantages to the itinerant life I had been leading, there was one big advantage. It was a quick way to escape the problems one had, though often it proved to be a case of out of the frying pan into the fire.

In some respects I never felt a sense of belonging in this new world, though I had been told that this was where my roots were. I now know that people always on the move often find it difficult settling in one place. The desire to keep moving becomes part of your life; maybe one never feels that one has arrived home. This sort of feeling is often experienced by emigrants who on returning to their country of origin feel they do not belong. They then find that they cannot settle in the place from whence they started, so they keep on searching for the roots they have lost

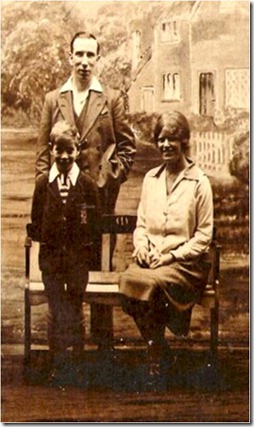

In some respects I never felt a sense of belonging in this new world, though I had been told that this was where my roots were. I now know that people always on the move often find it difficult settling in one place. The desire to keep moving becomes part of your life; maybe one never feels that one has arrived home. This sort of feeling is often experienced by emigrants who on returning to their country of origin feel they do not belong. They then find that they cannot settle in the place from whence they started, so they keep on searching for the roots they have lost ← I estimate this picture was taken about the end of 1941 or early 1942. My brother Paul looks to be a year old, or a little more.

When you look and sound differently, and do not behave as others do the society in which you live rejects you; throws you out of the nest so to speak. For quite some time this is the problem I had, especially where other children were concerned. There were relatives who were friendly and didn’t treat me as though I was an alien from another planet. Though this does not mean to say that I felt a complete affinity with many of them; they were so different, and I am sure they thought the same of me as well. I had to learn to live in this new environment, but looking back now I can see that I never completely adjusted to it. This was not my world, and when I moved on, I had no regrets and never looked back.

Aunt Jin was a large part of our lives at this time, and she provided much of the strength and support that we needed; especially for my mother. Young though I was I also sensed her strength, and her presence gave me confidence, and helped me adjust. Her husband Charlie Nicklin was a quiet man who had little to say, and was content to leave the running of things to his wife. He worked for the city council as a driver, and was what one would describe as the complete handy man. It was typical of him, that while others were installing their Anderson air raid shelters with as little inconvenience and effort as possible, Charlie made his a work of art. It was not buried in a shallow hole with a quantity of soil thrown over it; his was buried with at least six feet of cover over the roof, including a slab of reinforced concrete. There were steps leading down to the entrance, and he installed a concrete floor, bunks, and a light. Also included was an air pipe in case of complete burial. Above it a neat little lawn with flowers around to disguise what lay beneath. He had been in the trenches in the First World War, which is possibly why he took so much trouble to make his shelter safe and comfortable.

This is a picture of my Auntie Jin, (The eldest of the Jones children,) Uncle Charlie and my cousin Douglas. It was taken in 1929 at one of the seaside photographic studios when they were on holiday at Blackpool.

Charlie never talked to me like my Uncle Bill had done at Derby, but he was a kind man, and he often did things for me that made me his friend for life. On one occasion he gave me a rifle and bayonet he had made for me and it was so real to look at that I was totally overcome with his skill. It was a Lee-Enfield rifle, as used by the British Army, carved from wood, and painted to look almost genuine. I was proud to do my arms drill with it for his amusement, though I must confess to some disappointment, that I could not shoot real bullets with it. Occasionally I asked him to tell me about his war and what it had been like. Like most of those that served their country, he was reluctant to talk about it. Charlie was not a talker, though he was not without a sense of humour.

One day I saw him without his false teeth, and being curious like most small boys, I asked him how it was that he had no teeth. He looked at me with a very serious expression, and said “When I was in the trenches I was foolish enough to stick my head up to see what was happening, and a Jerry kicked my teeth out.” Another thing that comes to mind when I think of Uncle Charlie was his liking for beer. This liking was not allowed to get out of control, Aunty Jin saw to that, but he was allowed his ration on a Sunday. He had two quart flagons, one with a sherry label on it, and one entitled port. These containers were taken to the outdoor beer shop on Sunday evening and filled, one with best bitter beer, and the other with the best mild beer. Occasionally I was trusted with this very important service, and I was always happy to do it. Maybe I was willing because I was always rewarded with a packet of ‘Smiths’ crisps, with its small twists of blue paper which contained the salt.

My description of the Nicklin family would not be complete without mentioning their son Douglas. At this point in my story Douglas was a young man about 18/19 years old, he was medium height, and with fair hair like his mother. In character he was much like his father and he didn’t talk very much. Perhaps he was a little shy, or possibly just the strong and silent type. - In later years he married a strong and dominant woman, and assumed a role much as his father had done. - About a year after I arrived on the scene, Douglas was called up, and being a radio technician. He served in the REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers) becoming something of a communications expert. Most of his service was in the Mediterranean Theatre, including a period in what was then Palestine. His mention in this story is important I believe in one respect, and that is because he played the piano accordion. The instrument he owned was a beautiful full sized (120 button bass) German Honer, and he could play it very well indeed. His mother had kept his nose firmly adhered to the musical grind stone, and as a result he had all the certificates for theory right up to the final ‘Cap and Gown’. Sadly this final objective he failed to achieve, the reason being his inability to play from memory. The final test required the player to perform a piece for the judges and poor Douglas could not play a note unless he had the musical score in front of him.

No comments:

Post a Comment